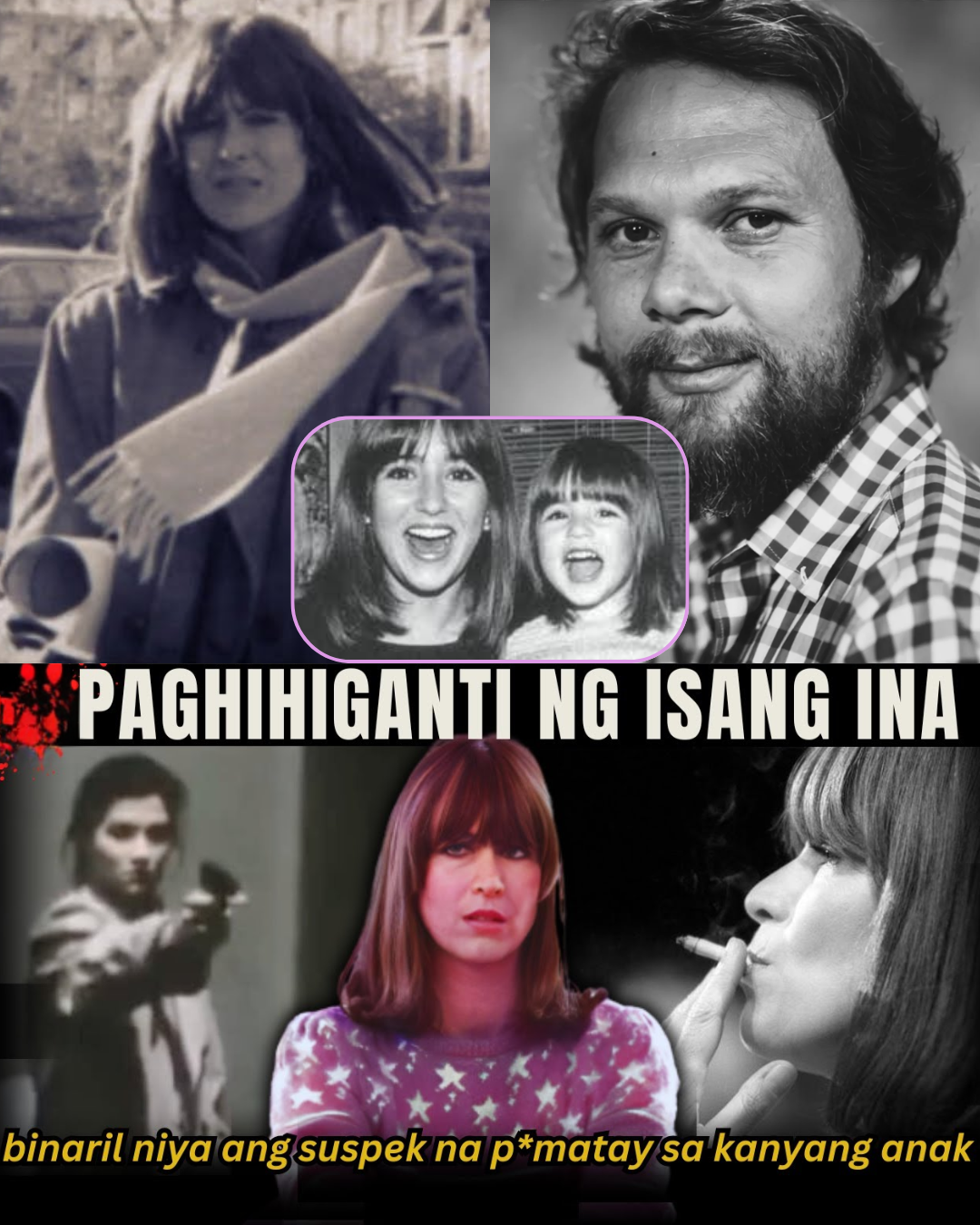

On a cold, rainy morning on March 6, 1981, the third day of a harrowing trial, the Lübeck District Courthouse was quiet. Klaus Grabowski, a 35-year-old man accused of the brutal murder of a 7-year-old girl, was led to his seat.

He sat with his back to the entrance. A moment later, the child’s mother, a 30-year-old waitress named Marian Bachmeier, walked into the room. She calmly walked up behind Grabowski, pulled a Beretta pistol from her purse, and fired eight times.

Seven bullets struck Grabowski in the back. He slumped forward, dead before he hit the floor. As chaos erupted, Marian dropped the gun and surrendered to an officer. “I wanted to shoot him in the face,” she stated, her voice devoid of emotion, “but he was turned… I hope he’s dead.”

This single act of courtroom vigilantism would stun Germany and turn Marian Bachmeier into one of the most polarizing figures of the 20th century. Was she a cold-blooded killer or a grieving mother who delivered the justice the system had denied her? The answer, like the woman herself, is profoundly complex.

A Life Forged in Trauma

Marian Bachmeier’s life was a story of survival long before her daughter’s tragic death. Born in 1950, her parents were refugees from East Prussia. Her father, a former soldier, returned from imprisonment as an alcoholic, spending his time in bars and directing his aggression at his family.

After he abandoned them, Marian’s mother remarried, but the new stepfather was even more cruel, subjecting Marian to terrible abuse. Her own mother, bitter and broken, blamed Marian for all their misfortunes and eventually kicked her out.

Her teenage years were a blur of instability. At 16, she became pregnant and gave the child up for adoption. At 18, she was pregnant again by her boyfriend. But just before she was due to give birth, she was brutally raped at a disco. Traumatized and fearing the attack would destroy her relationship, she gave that second child up for adoption as well.

In 1972, at 22, Marian was working as a waitress at Tipas, a local bar, and was in an on-again, off-again relationship with the manager. When she became pregnant a third time, something shifted. This child, she decided, would be her redemption. This one she would keep.

After her daughter, Anna, was born on November 14, 1972, Marian had herself sterilized, permanently ending her ability to have children. Anna was her last chance.

A Bohemian Life and a Fateful Fight

Anna became the center of Marian’s world. But as a single mother, Marian had to work. She brought Anna to the Tipas bar, where the little girl literally grew up, often sleeping on a bench while her mother served drinks into the early morning.

Anna was known by patrons as a bright, happy, and free-spirited child, but one living an unconventional, and arguably neglected, life. Realizing the situation was not ideal, Marian had even begun talks with a couple to have Anna placed in foster care.

On May 5, 1980, Marian and 7-year-old Anna had an argument. In defiance, Anna skipped school. She spent the day playing on the street, visiting a friend’s house (who was at school), and talking to neighbors. One of those neighbors was 35-year-old Klaus Grabowski. Anna knew him and would often ask to play with his cat.

That day, she crossed paths with him and asked to see the animal. He invited her up to his apartment. Hours later, Marian returned from a photoshoot for a local paper and realized Anna was gone. By that night, she had filed a missing person’s report.

A Predator, a Confession, and a Systemic Failure

The next afternoon, a woman walked into the police station. It was Grabowski’s girlfriend. She told police that Grabowski had confessed to a monstrous crime: he had killed Anna.

According to her statement, Grabowski had lured Anna to his apartment, and at some point, strangled her to death with a pair of his girlfriend’s stockings.

While the girlfriend was at the police station, Grabowski stuffed Anna’s small body into a cardboard box, tied her “like a pig,” put the box on his bicycle, and rode to a nearby canal, where he buried her in a shallow grave. He left a note for his girlfriend asking her to meet him. Police, alerted by the girlfriend, went to the meeting spot and arrested him.

The public was horrified, but the true shock came when Grabowski’s past was revealed. He had a long history of sex offenses against children. In 1975, after abusing two girls, a psychological evaluation deemed him a “sex addict” (pedophile) and a high danger to the public. He was sentenced to a psychological facility.

This is where the justice system failed. Grabowski was given a choice: a long-term stay, or “early release” if he agreed to chemical castration. He chose the “treatment.”

He was released in 1978 with zero psychological follow-up. Just two years later, in March 1980, Grabowski went to a urologist, lied that he was receiving psychiatric care, complained of side effects, and said he and his fiancée wanted to start a family. He requested hormone treatments to reverse the chemical castration. The court approved.

Weeks after receiving the testosterone treatment, he murdered Anna.

The Trial and the Tipping Point

The trial began in March 1981. The media coverage was relentless, and much of it was cruel. Reports painted Anna as a “street kid” and Marian as a negligent, part-time mother who worked in a bar.

Marian sat in the front row every day, forced to listen to the agonizing details of her daughter’s last moments while also being implicitly blamed for them by the press. She often yelled out at Grabowski in court.

Grabowski’s defense was grotesque. He claimed that Anna, 7 years old, had threatened to tell her mother he molested her unless he gave her money. He claimed he “panicked” because he feared going back to prison, so he strangled her.

On the second day of the trial, the urologist testified, revealing how Grabowski had lied to the court to get the testosterone that reversed his treatment. Public outrage exploded. The case was no longer just about a murder; it was about a legal system that had protected a predator and failed a child.

On the third day, just before the session began, Marian overheard a legal discussion. She misunderstood, believing that Grabowski was about to take the stand and publicly testify that her 7-year-old daughter had blackmailed him.

For Marian, a survivor of abuse herself, this final, disgusting lie was more than she could bear. The system had failed to protect Anna in life, and now it was about to fail her in death by allowing her killer to destroy her memory.

She decided, in that moment, that if the court would not provide justice, she would.

A Nation Divided

Marian’s act of vengeance turned her into a national folk hero overnight. The public, already incensed by the system’s failures, overwhelmingly sided with her. She was dubbed the “Revenge Mother.” Donations to cover her legal fees poured in, totaling over 100,000 German Marks. But the legal system was in a bind.

In the eyes of the law, Klaus Grabowski died an innocent man—his trial was not complete, and he had not been convicted. The state could not simply pardon Marian; to do so would be to endorse vigilante justice.

Marian’s own trial, which began in 1983, was a spectacle. The prosecution argued for first-degree murder, claiming the act was premeditated. They pointed out that she had bought the gun and practiced shooting it.

Her defense argued for manslaughter, claiming she acted on an uncontrollable, emotional impulse, driven by trauma. The prosecution, once again, attacked her character, arguing she was a negligent mother who acted not out of grief, but out of guilt for failing her daughter.

In the end, the court sided with the defense. The judge dismissed the murder charge, acknowledging the extreme trauma Marian had endured. She was found guilty of manslaughter and unlawful possession of a firearm and sentenced to six years.

After serving part of her sentence in a psychiatric facility, Marian was released for good behavior in June 1985. She sold her life story to Stern magazine, married, and moved to Nigeria, though the marriage was short-lived. She later moved to Italy, working as a caregiver.

Marian Bachmeier was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and returned to Germany, where she died in 1996 at the age of 46. In an interview, she said she was sad about what she had done, but she was not sad that Grabowski was dead.

She was buried in the same cemetery plot as her daughter, Anna, the child she had loved imperfectly, but fiercely, and for whom she had sacrificed her own freedom.

News

The Toxic Price of Rejection: OFW’s Remains Found in a Septic Tank After Coworker’s Unwanted Advances

South Korea, a hub for Asian development, represents a major aspiration for many Filipino Overseas Workers (OFWs), who seek employment…

The Final Boundary: How a Starving Tricycle Driver Exacted Vengeance at a Homecoming Party

On November 28, 2009, in Angat, Bulacan, a lavish homecoming party for two returning travelers ended in a catastrophic tragedy….

The 12-Year Ghost: Why the Woman Behind Vegas’s ‘Perfect Crime’ Chose Prison Over Freedom

On October 1, 1993, at the Circus Circus Casino in Las Vegas, a crime unfolded in minutes that would be…

The Fatal Soulmate: How a British Expat’s Search for Love Online Became a $1 Million Homicide Trap

In 2020, in a comfortable apartment overlooking the city of Canberra, Australia, 58-year-old British expatriate Henrick Collins lived a successful…

The Cost of Negligence: Firefighter Ho Wai-Ho’s Tragic Sacrifice in Hong Kong’s Inferno

The catastrophic fire that engulfed seven towers of the Wang Fook Court residential complex in Hong Kong was a disaster…

The KimPau Phenomenon: How “The A-List” Sparked Queen Kim Chiu’s Fierce Career Revolution

The Filipino entertainment industry is currently witnessing a stunning career metamorphosis, all thanks to the sheer, raw power of the…

End of content

No more pages to load