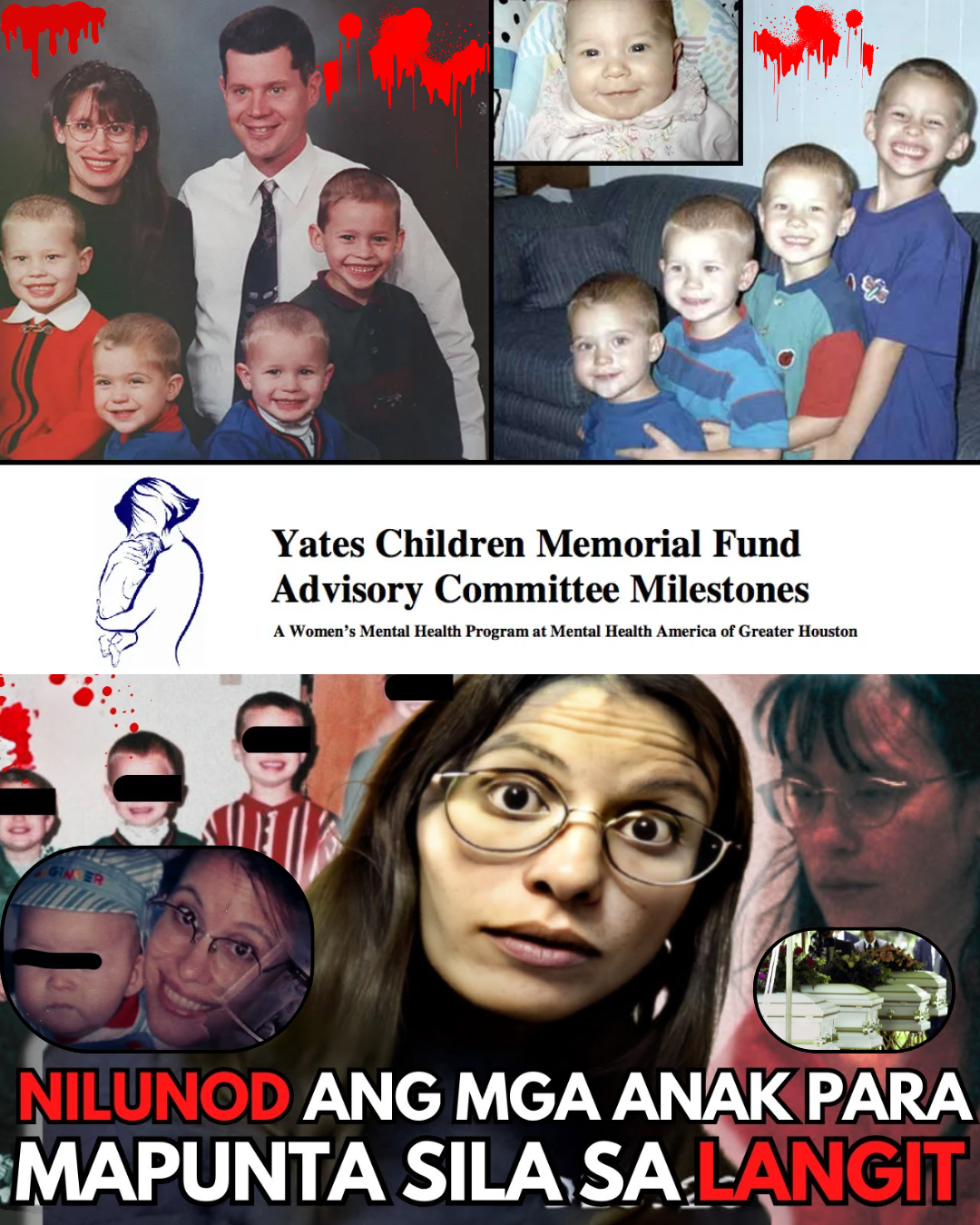

Andrea Pia Kennedy, born July 2, 1964, in Houston, Texas, was the youngest of five children. Described as happy in her early years, she began experiencing profound sadness in high school and was diagnosed with depression at 17. Despite this, she excelled academically, graduating as valedictorian in 1982. She pursued nursing, earning her degree and working for eight years at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

In 1989, she met Russell “Rusty” Yates, an engineer. They married in 1993, and Andrea stopped working to become a full-time homemaker. Deeply religious, the couple embraced the biblical injunction to “be fruitful and multiply,” deciding to have as many children as God provided. They bought a four-bedroom house and hosted Bible studies multiple times a week.

Their first child, Noah, was born in 1994. Shortly after, Rusty accepted a job in Florida, and the young family moved into a small mobile home. It was during this time that Andrea first confided in Rusty about experiencing disturbing hallucinations involving knives and urges to harm others.

Despite these troubling signs, their family continued to grow rapidly. John was born in 1995, followed by Paul in 1997 after a miscarriage. The family returned to Houston, living temporarily in a converted bus. Luke arrived in 1999.

After Luke’s birth, Andrea began homeschooling Noah while battling what was later identified as severe postpartum depression (PPD). This condition, often triggered by hormonal shifts after childbirth, can cause intense sadness, anxiety, and, in severe cases, psychosis. On June 16, 1999, Rusty found Andrea shaking uncontrollably and biting her own fingers.

The next day, she was hospitalized after overdosing on Trazodone, an antidepressant. She was diagnosed with a major depressive disorder. Upon release, her mental state remained fragile; she repeatedly begged Rusty to let her pass away and attempted to take her own life again. Her distress manifested physically—compulsively scratching her scalp until bald patches formed.

She was admitted to a psychiatric facility where she received antipsychotic medications, including Haldol. Doctors updated her diagnosis to include postpartum psychosis and possible schizophrenia.

Her condition stabilized, and she was released with instructions to continue medication. Crucially, her psychiatrist, Dr. Eileen Starbranch, strongly advised the couple against having any more children, warning that another pregnancy would almost certainly trigger severe psychotic depression.

Seeking a fresh start, the family moved into a small house. Andrea’s condition seemed to improve, but the couple tragically ignored Dr. Starbranch’s warning. Andrea stopped taking Haldol in March 2000. On November 30, 2000, she gave birth to their fifth child, Mary. Initially, Andrea seemed to cope well, but the de@th of her father in March 2001 sent her spiraling back into psychosis.

She resumed self-harming behaviors, obsessively read the Bible, neglected baby Mary, and experienced intense hallucinations, believing spy cameras monitored her every move and TV characters were calling her a bad mother. Rusty admitted her to Devereux Advanced Behavioral Health Texas under the care of a new psychiatrist, Dr. Mohammed Saeed.

After only a week, despite Andrea’s severe state, Dr. Saeed released her. Her condition worsened immediately. On May 3, 2001, she was readmitted after Rusty suspected she tried to drown herself in the bathtub. Astonishingly, on June 4, Dr. Saeed discontinued Andrea’s primary antipsychotic medication, Haldol, advising her instead to simply “think positive thoughts.”

On the morning of June 20, 2001, Rusty Yates left for work, disregarding Dr. Saeed’s explicit instruction not to leave Andrea unattended with the children. His mother was scheduled to arrive an hour later to help. In that one-hour window, the unthinkable happened.

Andrea systematically drowned her five children. She filled the bathtub with water. She started with the younger boys: John (5), Paul (3), and Luke (2). After each child stopped breathing, she carried their small bodies to the master bedroom and laid them on the bed, covering them with a sheet.

She then drowned baby Mary (6 months), leaving her body floating in the tub. Seven-year-old Noah walked in, saw his sister, and asked what was wrong. Realizing the horror, he tried to run, but Andrea caught him, struggled with him, and drowned him too. She then placed his body on the bed with his brothers and carried Mary’s body from the tub, laying her beside them. Afterward, she calmly called 911.

“I need a police officer… I just ended the l!fe of my kids,” she told the dispatcher. She then called Rusty, simply telling him, “It’s time. You need to come home.” When Rusty arrived, police were already there, preventing him from entering the house where the horrific scene was being processed.

Andrea readily confessed, explaining her actions with chilling clarity. The news shocked the nation. Initial media portrayals painted her as a monster. However, Rusty’s immediate public statements about Andrea’s long battle with severe mental illness began to shift the narrative, sparking a fierce debate: was she evil or profoundly ill?

Prosecutors pursued capital charges, arguing Andrea knew right from wrong, evidenced by her waiting for Rusty to leave and locking the family dog away before the drownings. Her defense team prepared an insanity defense. Declared competent to stand trial after months of treatment, Andrea faced a jury in 2002.

The prosecution emphasized Andrea’s methodical actions as proof of sanity. The defense presented extensive evidence of her psychosis, delusions, and history of hospitalizations. A key, and later controversial, element involved prosecution psychiatrist Dr. Park Dietz, who testified Andrea might have been inspired by a “Law & Order” episode depicting a similar crime with an insanity acquittal.

The jury found Andrea guilty of capital offenses but opted against the de@th penalty, sentencing her to life in prison with parole eligibility after 40 years. While incarcerated, Andrea continued to struggle, attempting self-harm by refusing food.

She revealed to psychiatrists her long-standing delusion that her children were “not developing correctly” and were destined for hell. She believed ending their lives was an act of mercy, ensuring their salvation.

Andrea’s lawyers appealed the verdict. In 2005, an appellate court overturned her conviction. The basis? Dr. Dietz’s testimony about the “Law & Order” episode was false; no such episode existed. The court ruled this misinformation could have improperly influenced the jury.

A second trial began in 2006. This time, the defense focused even more heavily on Andrea’s documented history of psychosis.

Dr. Saeed faced scrutiny for his treatment decisions, particularly discontinuing Haldol. Rusty Yates also testified, facing difficult questions about his role, his awareness of Andrea’s condition, and his adherence (or lack thereof) to medical advice.

He partially blamed Dr. Saeed and denied knowing the full severity of Andrea’s psychosis, a claim contradicted by Andrea’s statements that Rusty knew about her condition but encouraged more children due to their religious beliefs.

The influence of Michael Woroniecki, an itinerant preacher whose newsletters the Yates followed, also came under examination. Woroniecki’s teachings emphasized female submission and the damnation of disobedient children, themes potentially exacerbating Andrea’s delusions about needing to save her children from hell.

On July 26, 2006, after three days of deliberation, the second jury found Andrea Yates not guilty by reason of insanity. She was committed to the North Texas State Hospital, a high-security mental health facility, later transferred to the lower-security Kerrville State Hospital in 2007.

Rusty Yates divorced Andrea in 2005 and remarried in 2006. Andrea remains at Kerrville State Hospital. Her requests for passes to attend off-site church services or group outings have been denied or withdrawn due to public opposition.

Annually, she waives her right to a review hearing that could potentially lead to her release, indicating she may not feel ready or believe release is appropriate.

According to her attorney, she lives a quiet life within the facility, making crafts like cards and aprons, which are sold for charity. She reportedly watches videos of her children and finds solace when told people visit their gravesites.

The Andrea Yates case remains a profoundly tragic landmark, forcing society to confront the devastating realities of severe maternal mental illness and the complex intersection of faith, responsibility, and the legal definition of insanity.

News

The Toxic Price of Rejection: OFW’s Remains Found in a Septic Tank After Coworker’s Unwanted Advances

South Korea, a hub for Asian development, represents a major aspiration for many Filipino Overseas Workers (OFWs), who seek employment…

The Final Boundary: How a Starving Tricycle Driver Exacted Vengeance at a Homecoming Party

On November 28, 2009, in Angat, Bulacan, a lavish homecoming party for two returning travelers ended in a catastrophic tragedy….

The 12-Year Ghost: Why the Woman Behind Vegas’s ‘Perfect Crime’ Chose Prison Over Freedom

On October 1, 1993, at the Circus Circus Casino in Las Vegas, a crime unfolded in minutes that would be…

The Fatal Soulmate: How a British Expat’s Search for Love Online Became a $1 Million Homicide Trap

In 2020, in a comfortable apartment overlooking the city of Canberra, Australia, 58-year-old British expatriate Henrick Collins lived a successful…

The Cost of Negligence: Firefighter Ho Wai-Ho’s Tragic Sacrifice in Hong Kong’s Inferno

The catastrophic fire that engulfed seven towers of the Wang Fook Court residential complex in Hong Kong was a disaster…

The KimPau Phenomenon: How “The A-List” Sparked Queen Kim Chiu’s Fierce Career Revolution

The Filipino entertainment industry is currently witnessing a stunning career metamorphosis, all thanks to the sheer, raw power of the…

End of content

No more pages to load