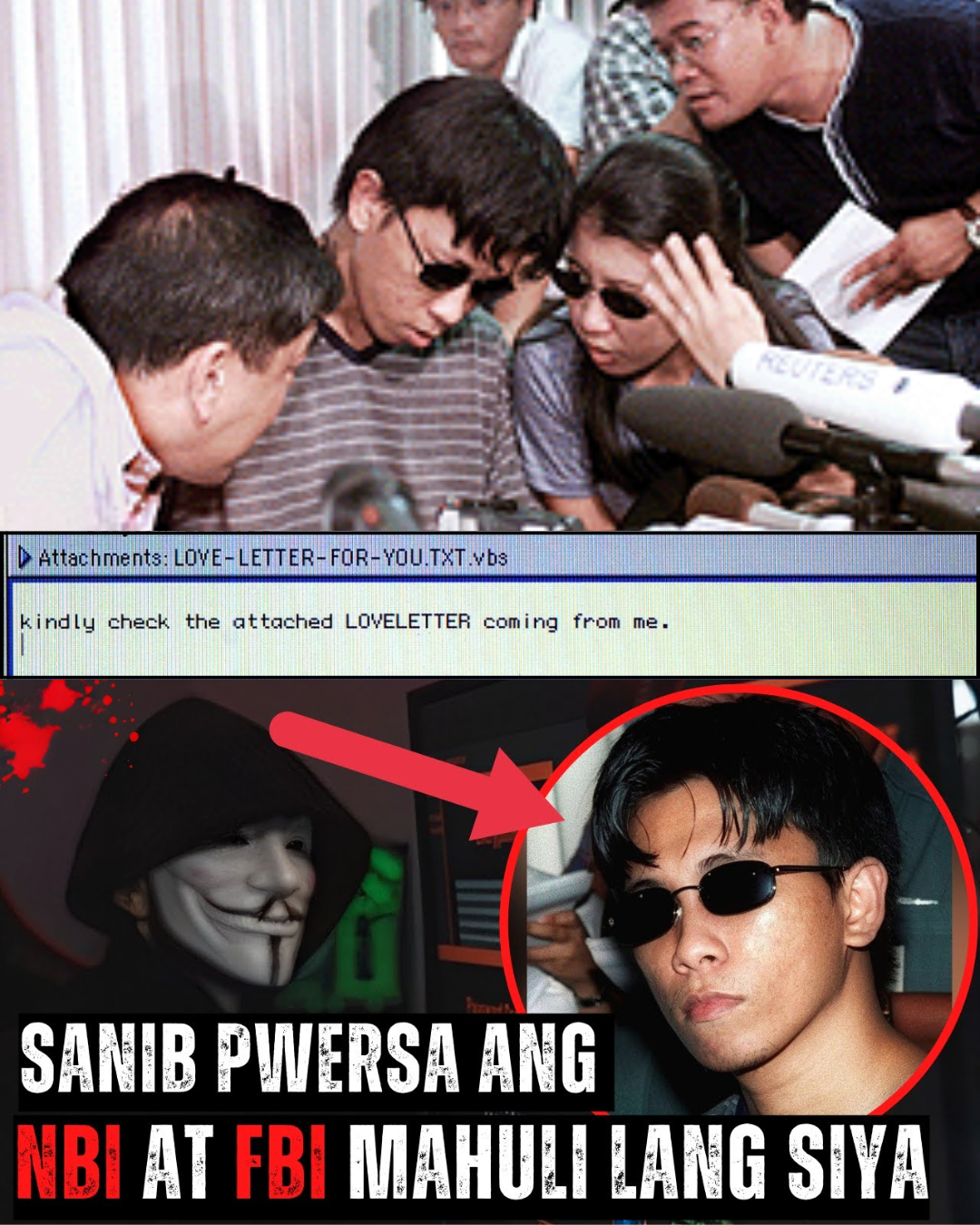

In the year 2000, a digital pandemic swept the globe. It didn’t attack animals or humans, but computers, crippling systems worldwide.

The damage was estimated between $5 to $8.7 billion, with cleanup costs soaring to $10 to $15 billion.

Institutions like the Pentagon, the CIA, the British Parliament, and countless major corporations were forced to shut down their email systems to staunch the bleeding.

Shockingly, the source of this global mayhem was traced back to a humble apartment in Pandacan, Manila, Philippines – the home of the alleged programmers behind the destructive code.

This is the story of the ILOVEYOU virus, deemed one of the top 10 most virulent computer viruses in history.

Onel de Guzman grew up in Pandacan, Manila, part of a lower-middle-class family. Born the youngest and only son, his curiosity gravitated towards computers early on.

At just 12, instead of playing outside, he was fascinated by his older sister Irene’s computer, trying to understand how it worked.

After high school, he naturally pursued programming at AMA Computer College. His curiosity deepened into an obsession.

He devoured programming books – his professor’s, his sister’s – and spent hours in bookstores absorbing knowledge. Cyber cafes became his classrooms, watching tutorials and learning techniques from programmers worldwide.

Beyond coding, Onel loved the popular video games of the era, like Street Fighter. Soon, reading and watching weren’t enough; he needed to apply his knowledge.

Feeling constrained by school rules, he secretly used his sister’s computer, testing commands and codes learned from textbooks and online videos. He was surprised by his success; his tests worked without crashing the machine.

Even before graduating, Onel was described as a computer whiz. He reportedly developed programs to bypass security systems, gaining access to restricted information often used for illicit websites.

He created a program to stealthily acquire internet account passwords. He explained it was easy back then; people were easily fooled by attractive profile pictures.

He would enter chat rooms using a found photo, send his target a file, and once opened, gain remote control of their computer via hidden software. His goal? Stealing internet passwords, as he couldn’t afford his own account.

Despite his programming talent, Onel struggled academically. Weeks before graduation, his thesis proposal, ominously titled “Trojan Password Stealer,” was rejected by the college dean.

The dean’s decision, according to AMA’s Senior Vice President later, was based on the school’s refusal to endorse unethical activities.

Days after the rejection, just before graduation, Onel visited a high school friend. While he was drinking beer and eating isaw (grilled intestines), halfway across the world in Hong Kong, an employee opened a work email.

The subject line was simple, intriguing: “ILOVEYOU.” The message read, “Kindly check the attached Love Letter coming from me.”

The unsuspecting employee opened the attachment. Unbeknownst to them, they had just unleashed a highly destructive computer worm.

Within hours, it spread through their office, eventually damaging 13,000 computers. That same day, the worm jumped continents, reaching Europe and America.

In just ten days, the estimated damage hit 15 million computers. IT experts globally scrambled to contain the outbreak.

The Pentagon, CIA, and British Parliament shut down email systems to protect critical files. Major corporations followed suit, ordering temporary server shutdowns.

Why was it so devastating? At the time, Windows dominated 95% of the personal computer market. Many offices used bundled Microsoft Office plans that included the Outlook email client.

Experts examining the source code, dubbed the “Love Bug worm” or “ILOVEYOU virus,” found it was crafted using readily available malicious software tools and Visual Basic scripting (VBS).

For non-programmers, the file appeared harmless. The recent release of Windows 2000 compounded the problem. This new operating system hid file extensions by default, unlike previous versions where it was an option.

The programmer exploited this vulnerability. The email attachment, named “LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT.vbs,” appeared to many users simply as “LOVE-LETTER-FOR-YOU.TXT” – a harmless text file.

Curiosity or the hope of a secret admirer led millions to click. Once opened, the worm executed its malicious code autonomously.

First, it duplicated itself. Then, it overwrote personal files – audio, images, documents – across the computer’s directories. It altered registration keys, confusing the operating system.

Critically, it automatically emailed itself to every contact in the user’s Outlook address book, ensuring exponential spread. Finally, it created a program named “WIN-BUGSFIX.EXE,” which appeared helpful but secretly stole saved passwords.

IT experts labeled it catastrophic by design. The FBI launched an immediate investigation, quickly zeroing in on the Philippines due to clues embedded in the email itself: the phrase “Manila, Philippines” and “I hate to go to school.”

The FBI dispatched agents to Manila, collaborating with the Philippines’ National Bureau of Investigation (NBI). NBI Director Federico Opinion Jr. formed two dedicated units: International Police Liaison and Anti-Fraud & Computer Crimes Division.

Their mission was urgent. Each passing day meant more potential damage, not just to businesses and governments, but to universities and hospitals.

They traced the hacker’s Internet Service Provider (ISP) to Supernet. The COO of Access Net Inc., Supernet’s owner, stated the hacker likely used fake email addresses and was possibly a prepaid internet user.

Working with various Philippine ISPs, the NBI discovered the Love Bug worm had been uploaded to a Sky Internet server on April 28th. The rapid spread overwhelmed their technicians, forcing them to suspend email servers.

Antivirus giant Trend Micro reported nearly 2 million affected files within their systems alone, with damages in the millions. Asia was less impacted initially, as the attack hit on a Friday, but thousands of files were still corrupted in Japan and China. The White House confirmed its systems remained secure.

Back in Pandacan, Onel de Guzman watched the news with growing anxiety as the global manhunt intensified. On May 8, 2000, authorities raided his sister Irene’s apartment.

Onel, Irene, and her boyfriend, Reonel Ramones, were startled by the forced entry and arrested. Their faces were soon plastered across newspapers and news broadcasts.

The NBI Director announced they had obtained a warrant after computer experts traced the worm’s origin to that very apartment. Ramones, a bank employee, denied any involvement, stating he lacked the skills to create such a worm.

When questioned, Onel was confronted with his rejected thesis. Authorities highlighted the similarities between his password-stealing proposal and the Love Bug’s password-theft component.

Onel didn’t confess but admitted his thesis project was a “pastime” solely intended to steal internet access for free use, clarifying it contained no destructive code. He claimed he never released his program and suggested any release must have been accidental.

He theorized someone else – a classmate, perhaps even his sister – might have accessed his program on the computer where it was installed and modified it without understanding the code, causing it to malfunction.

Both Onel and Ramones were initially charged with credit card fraud and violations of the Access Devices Regulation Act of 1998 – a law primarily targeting credit card scams.

Why these charges? Because in May 2000, the Philippines had no laws against hacking or creating computer viruses. It simply wasn’t illegal.

Prosecutors, under immense international pressure, scrambled to find existing laws that could tangentially apply. Credit card fraud was the closest fit they could find.

The attempt failed spectacularly. The judge dismissed the charges the day after their arrest, stating there was insufficient evidence and that credit card fraud laws did not cover computer viruses or cybercrimes.

Onel and Ramones walked free. Due to the legal loophole, no trial would occur. It remained officially unproven whether they were responsible.

The outcome sparked varied reactions. AMA Computer College distanced itself, stating they taught ethics, not “Virus 101.” Onel retreated from public view.

Five months later, in October 2000, he gave an interview. Looking slightly different – shorter hair, heavier build – he attributed his weight gain to home cooking and spending time playing PlayStation.

He reiterated his uncertainty about whether the released Love Bug was truly his original program, suggesting modifications by others. He lamented that authorities never showed him the worm’s source code, which he could have used to confirm or deny authorship.

He mentioned receiving numerous job offers from major tech companies but declined them due to the ongoing legal uncertainty and his inherent shyness. He claimed he had stopped hacking.

Public opinion remained divided. Some Filipinos hailed him as a “national pride” and “genius” for proving Filipino ingenuity, even managing to penetrate the Pentagon’s systems. Classmates expressed pride.

Others condemned him. The director of McAfee’s antivirus team firmly believed Onel intentionally released the worm. Filipino web activists called him childish. A prominent businessman labeled hackers like him a menace whose creations only caused harm.

The Philippine Congress acted swiftly. Two months after the incident, they fast-tracked and passed Republic Act No. 8792, the E-commerce Law, finally criminalizing hacking and the creation of malicious software.

For two decades, the question of Onel’s true role lingered. Then, in May 2020, British reporter Geoff White published an article for the BBC. He had tracked Onel down.

After chasing false leads suggesting Onel had moved abroad or worked for Microsoft, White found him in April 2019, running a small cellphone repair shop in a mall in Quiapo, Manila.

In their conversation, Onel de Guzman, then 44, finally admitted it. He was the creator of the Love Bug worm.

He explained it was an enhanced version of his rejected thesis program. Internet access in the Philippines was expensive then, and his program was designed purely to steal passwords for free access.

Initially focused on local targets, in the spring of 2000, he modified the code. He added a command to automatically spread the worm via Outlook contacts, exploiting flaws in the newly released Windows 2000. He chose the “love” theme because he believed people were easily enticed by the prospect of romance.

He confirmed Ramones had no involvement. He never went back to school, opting to start his repair business instead. He expressed regret for unleashing the worm.

His confession reignited questions about potential prosecution under the new E-commerce Law. However, legal experts pointed to Article 3, Section 22 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution (prohibiting ex post facto laws). He could not be charged under a law that didn’t exist when the act was committed.

Extradition to the US was also impossible, as treaties require the act to be illegal in both countries at the time it occurred. While hacking was illegal in the US in 2000, it wasn’t in the Philippines until June 14, 2000, weeks after the Love Bug was released.

Onel de Guzman, the man who unleashed arguably the most damaging computer worm in history, remains a free man, running a small repair shop, a footnote in the annals of cyber history secured by a crucial legal loophole.

News

The Toxic Price of Rejection: OFW’s Remains Found in a Septic Tank After Coworker’s Unwanted Advances

South Korea, a hub for Asian development, represents a major aspiration for many Filipino Overseas Workers (OFWs), who seek employment…

The Final Boundary: How a Starving Tricycle Driver Exacted Vengeance at a Homecoming Party

On November 28, 2009, in Angat, Bulacan, a lavish homecoming party for two returning travelers ended in a catastrophic tragedy….

The 12-Year Ghost: Why the Woman Behind Vegas’s ‘Perfect Crime’ Chose Prison Over Freedom

On October 1, 1993, at the Circus Circus Casino in Las Vegas, a crime unfolded in minutes that would be…

The Fatal Soulmate: How a British Expat’s Search for Love Online Became a $1 Million Homicide Trap

In 2020, in a comfortable apartment overlooking the city of Canberra, Australia, 58-year-old British expatriate Henrick Collins lived a successful…

The Cost of Negligence: Firefighter Ho Wai-Ho’s Tragic Sacrifice in Hong Kong’s Inferno

The catastrophic fire that engulfed seven towers of the Wang Fook Court residential complex in Hong Kong was a disaster…

The KimPau Phenomenon: How “The A-List” Sparked Queen Kim Chiu’s Fierce Career Revolution

The Filipino entertainment industry is currently witnessing a stunning career metamorphosis, all thanks to the sheer, raw power of the…

End of content

No more pages to load